Spanish painter and illustrator. He studied at the Real Academia de S Fernando, Madrid, under Juan Antonio Ribera y Fernández and José de Madrazo y Agudo. He worked independently of court circles and achieved some fame but nevertheless died in such poverty that his burial was paid for by friends. He is often described as the last of the followers of Goya, in whose Caprichos and drawings he found inspiration for the genre scenes for which he became best known. Of these scenes of everyday life and customs the more interesting include The Beating (Madrid, Casón Buen Retiro) and Galician with Puppets (c. 1835; Madrid, Casón Buen Retiro).

Spanish painter and illustrator. He studied at the Real Academia de S Fernando, Madrid, under Juan Antonio Ribera y Fernández and José de Madrazo y Agudo. He worked independently of court circles and achieved some fame but nevertheless died in such poverty that his burial was paid for by friends. He is often described as the last of the followers of Goya, in whose Caprichos and drawings he found inspiration for the genre scenes for which he became best known. Of these scenes of everyday life and customs the more interesting include The Beating (Madrid, Casón Buen Retiro) and Galician with Puppets (c. 1835; Madrid, Casón Buen Retiro).

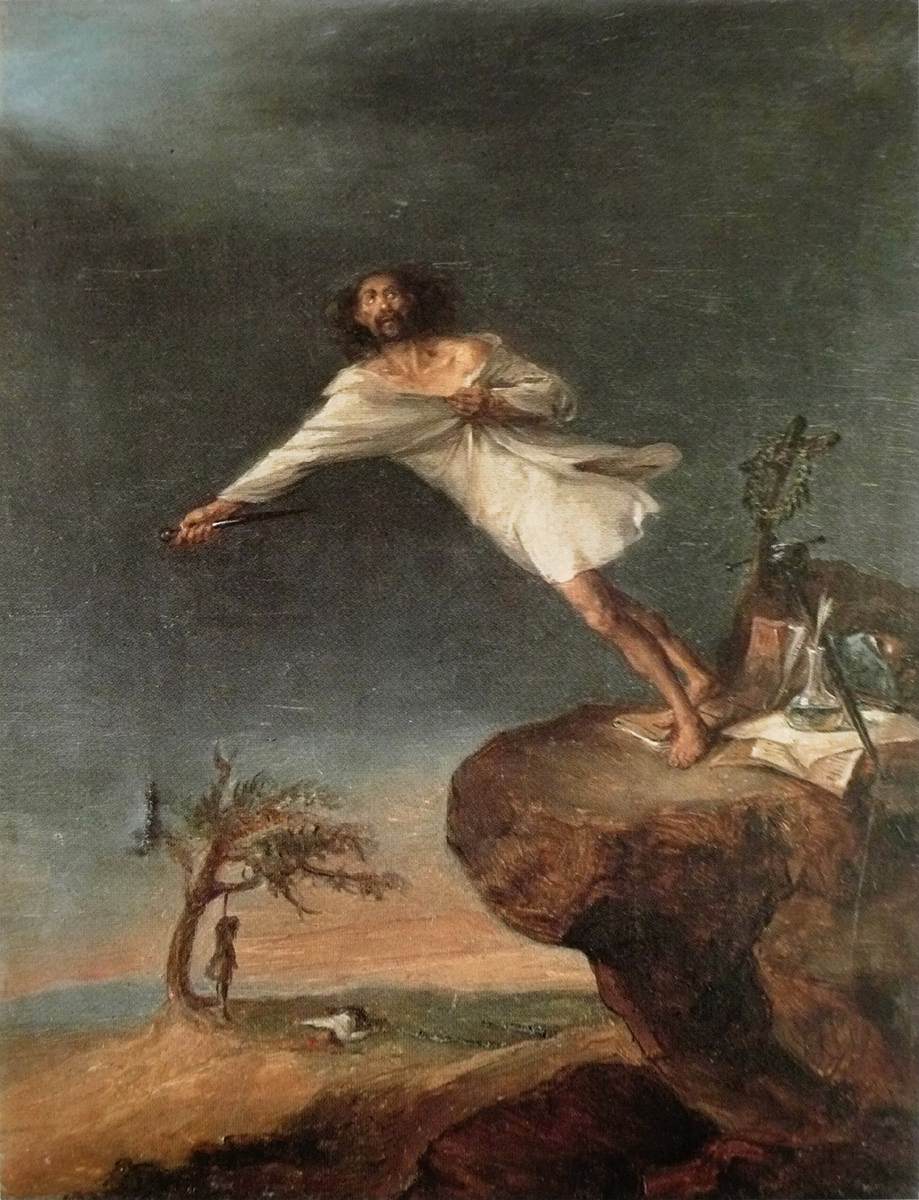

| Painting Name | Sátira del suicidio romántico (Satire on Romantic Suicide) |

| Painter Name | Leonardo Alenza |

| Completion Date | 1839 |

| Size | 36 x 28 cm |

| Technique | Oil |

| Material | Canvas |

| Current Location | Museo Romántico Madrid |

Alenza y Nieto’s numerous drawings include the illustrations for Alain-René Lesage’s Gil Blas (Madrid, 1840), for an edition of the poems of Francisco de Quevedo published by Castello and for the reviews Semanario pintoresco and El Reflejo. The painting Triumph of David (1842; Madrid, Real Academia San Fernando) led to his election as an Académico de mérito at the Real Academia de San Fernando in 1842, and he produced such portraits as that of Alejandro de la Pena (Madrid, Real Academia San Fernando) and a Self-portrait (Madrid, Casón Buen Retiro). His two canvases entitled Satire on Romantic Suicide (Madrid, Museo Romántico) are perhaps the most characteristic of his works.

Satires on love, or scornful impressions about hopeless romantics can be a controversial artistic indulgence. However, many greats have done just that. And when NIETO does his bit, it can be easy to pass it in the allowable category because it has a message. No matter how clichéd that sounds, the message for everyone is – that you are better off with any lack of hopelessness that you apparently suffer, especially when it comes to women or deep-seeded love.

Masculine in outlook, the painting could pass off even as a femininely dominatrix expression. No one making a satire unless it is categorized. When I first looked at our ‘suicidal Jesus’, (as the subject has been made to look like him), I never escaped the thought that the man could have made love his religion, and then a woman failed him as his Goddess. My earnest sympathy was evoked, but almost nipped in the bud when the painting took me to his face.

NIETO brings out a subtle balance in tonality, especially with the way he communicated his strokes. You can never miss the backdrop – silent as it always was. A silence that dominates everything inside the farthest periphery of the landscape.

A cliff is all there is for our suicidal lover to make things convenient. A dagger to make sure he has felt the pain, and gotten himself used to the trauma, which could have otherwise hit him upon striking the ground.

Hopeless and forlorn, his soul is on the way to disappearance, much like the unperturbed laws of nature. However, he is also not worthy of an enamel, panel or wood painting effort, because the edginess of canvas, and the satirical notes of NIETO’s brush-strokes makes the impression that we are mere witnesses in the pitfalls of hopeless lovers.